We are delighted to announce the arrival of an invaluable gift—the Erritzoe collection from the House of Bird Research in Denmark. Dr. Johannes Erritzoe has been a Research Affiliate of the University of Alaska Museum (Ornithology) for over 20 years, and his bird collection is an amazing scientific resource. Developed over decades of careful work, this research collection has already been important for scientific productivity. Its importance and use will grow considerably now that it is in Fairbanks, because it has not historically been online or in a public lending institution. The scientific gains for the Museum, for UAF, for this collection, and for ornithology are considerable.

The Erritzoe collection comprises over 8,800 meticulously prepared bird specimens and is highly complementary to the current UA Museum bird collection. A large proportion of Alaska birds are Holarctic in distribution. Many more are the easternmost representatives of Eurasian populations and their close relatives. As such, the Erritzoe collection, most of which is from the northwestern Palearctic, is an important scientific addition to our current holdings. In short, we cannot understand the similarities and uniquenesses of Alaska birds without using complementary material like this—much of which we’ve had to borrow in the past to work in the appropriate comparative framework. This collection is also a fantastic research resource for the study of northern birds and the ways in which climate change affects them.

The permitting and moving of such a large collection was especially challenging, and we thank the many people both in Denmark and the U.S. who helped us accomplish this task. Our next steps are to get the collection catalogued, integrated, and online so that it is widely available to researchers.

(See longer story below, with images.)

Behind the scenes

This long journey began when I (Kevin Winker) received an email from Johannes Erritzoe in response to the publication in 2000 of my how-to paper on bird specimen preparation. Johs is a master preparator, and we had a lot to discuss. Over the years since, Johs and his son Axel came over for a visit here, I’ve gone over there for visits, and we’ve exchanged specimens back and forth. We’ve also exchanged a lot of emails as we’ve corresponded through the years. Johs even convinced me to join him and others as a coauthor on a dictionary of ornithology.

Johs and his inimitable wife Helga, who is an amazing artist, wanted his collection to come to UAF when he was no longer able to work effectively with it. His health took some serious bumps as the world was emerging from covid, and he wrote and asked that we come and pack up his collection. This proved to be astonishingly difficult at that time, mostly because covid had shattered the supply chain, which means shipping. The collection is far too large to make air shipping a viable option. We struggled for over a year with one shipper as they tried to patch together a surface route before we had to abandon them and, with expert help, select another company.

Permitting was another logistics puzzle, but here again we had excellent help both from the Danish and U.S. authorities, who graciously answered all of our questions and enabled us to put together a permitting package and labeling protocols that would meet the expectations of both sides.

With the improving supply chain and a real go-getter spearheading our shipping logistics, everything finally came together in the fall of 2023. Jack Withrow and I went over to Taps, Denmark and packed up Johs’s marvelous collection. It was wonderful to see Johs, Helga, and Axel again, and Helga sat us all down to delicious lunches together every day.

Johs had spent lots of time and done an incredible job of preparing the specimens for shipping, and over the years he had catalogued them all, so we had an excellent database. Jack and I just had to sort which birds were optimally placed where (e.g., with CITES-listed specimens most accessible for inspection), get the labeling all correct, and get the specimens compacted a bit in volume so they would all fit into our 20-foot shipping container.

The House of Bird Research, with Jack Withrow and Johannes and Helga Erritzoe

Some of the details of that process I will never forget. As we put individual birds from trays into boxes, Johs would periodically tell us a story about a particularly memorable bird. One was a cuckoo chick, one of his first specimens, from 1948. He had set up a blind in his yard to watch, from dawn to dark, a host nest in which the cuckoo chick hatched and was growing. But it died, so he prepared it as a specimen. He was a young teenager at the time.

One day, Johs’s good friend Svend came over to assist. He was a real help, and we also had one of the best lunches I can recall, with great food, great stories, and a lot of laughing. Then we emptied the skeletons out of the basement. Johs preserved thousands of partial skeletons, and they were in boxes in the basement. Jack had the good idea to pass them up and out through the small windows at the top of the basement walls. We set up a work chain, with me making sure each box was mostly full (compacting among boxes), then passing them up and out to Svend, who put them in a wheelbarrow and transported them over to Jack in the carport, where he’d work his ‘Tetris’ skills getting them into pallet boxes. Each time Svend’s wheelbarrow was full, he’d cheerfully let me know, “I’m driving.”

We packed the collection box by box into 4-foot cubic pallet boxes and had the Erritzoe garage and carport filled with those when our 20-foot shipping container was dropped in the yard.

Our logistics nightmares included—of course—lost luggage. We worked for days without clean clothes or our equipment. That equipment included our most important supplies, like cinch straps, paper, printer, stickers, etc. Just as we were stalled by that, our bags arrived. It was like Christmas! We were then able to label the boxes and load the container. We were able to do that in one long day.

That night, we realized that because the container doors didn’t close tightly on that uneven surface, it was possible that rodents had gotten in. So we borrowed some traps from Johs and Helga, baited them with cheese, put them under the rear-most pallets, and, with great effort (a Jack and a jack), closed and locked the doors. And off Jack and I went—to Copenhagen and then home.

Sailing, sailing…

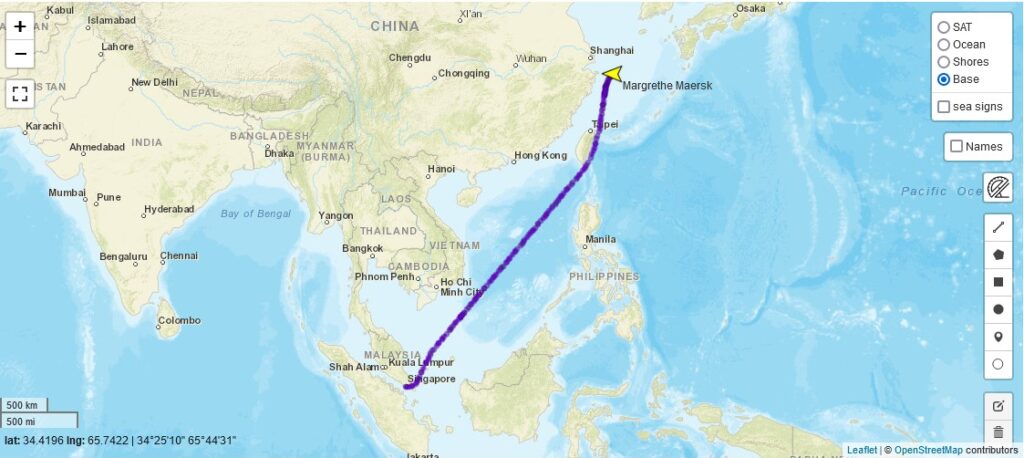

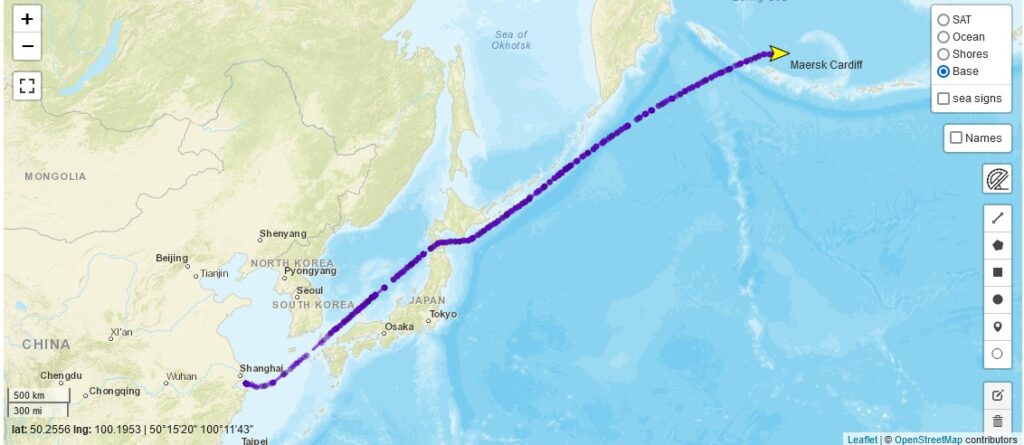

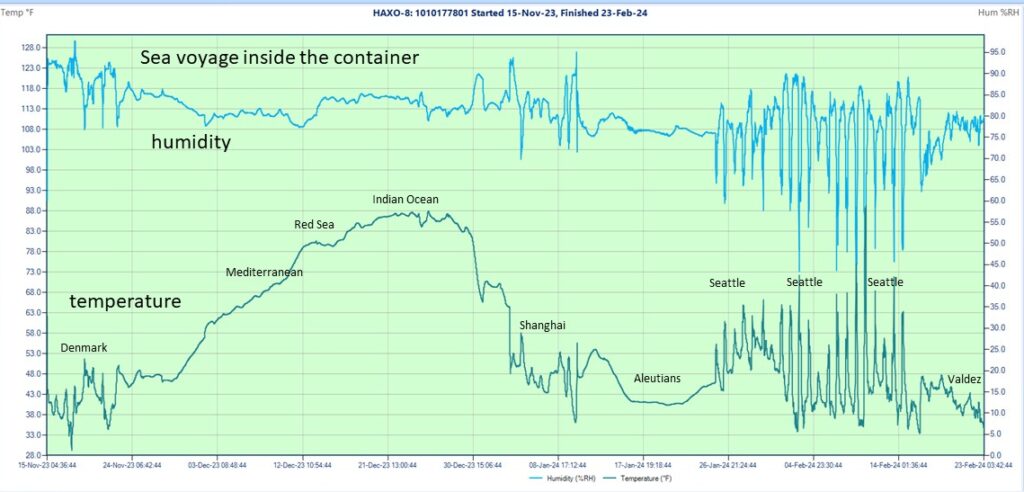

Shortly after our departure from Denmark, our container was hauled to a Danish port and loaded on the container ship Margrethe Maersk. This next stage was the nerve-wracking part of our effort. The collection was safe and sound at the House of Bird Research, but in transit many things could go wrong. So both in Denmark and in Alaska we carefully followed the ship’s progress daily online, first through the Mediterranean, then through the Suez Canal and into the Red Sea. Fortunately, she scooted through the southern Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden before the Houthi’s missiles caused a closure of that route. This was a close thing—she made it through with hours to spare, and on the journey back home she had to take the long route around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa. After clearing that conflict zone, on she went to Shanghai, where the container was dropped and a few days later picked up by the Maersk Cardiff. This vessel shot to the north on the Great Circle route to the North American port of Seattle. This route passes through the Aleutian Islands, so the collection first arrived in Alaska long before it arrived in Fairbanks. But after a quick journey through the Aleutians, she passed south of the Gulf of Alaska and on to Seattle.

After clearing that conflict zone, on she went to Shanghai, where the container was dropped and a few days later picked up by the Maersk Cardiff. This vessel shot to the north on the Great Circle route to the North American port of Seattle. This route passes through the Aleutian Islands, so the collection first arrived in Alaska long before it arrived in Fairbanks. But after a quick journey through the Aleutians, she passed south of the Gulf of Alaska and on to Seattle.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Law Enforcement folks in Seattle had asked Jack and I to go down to help them with the import inspection. So at the end of January we found ourselves in the temperate Seattle weather headed to a large Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) warehouse near the airport. There we found a great group of people, highly efficient at what they do. When the container doors were opened—first time since we’d closed and locked them in Denmark—we saw to our delight that everything had ridden beautifully. There was no water or water damage visible. Things were just as we’d left them, except that the cheese on the traps had gotten moldy.

The forklift drivers at this CBP warehouse are incredibly skilled. Jack and I wished we’d had them on the Denmark end, where we’d done everything manually. They quickly had most of the container unloaded and the boxes scattered out on the warehouse floor for opening and inspection. The whole thing only took an afternoon, and we were soon packed up and done and back to the airport to catch our evening flight. Very efficient. Our detailed discussions on permits and labeling before we packed it in November had helped immensely.

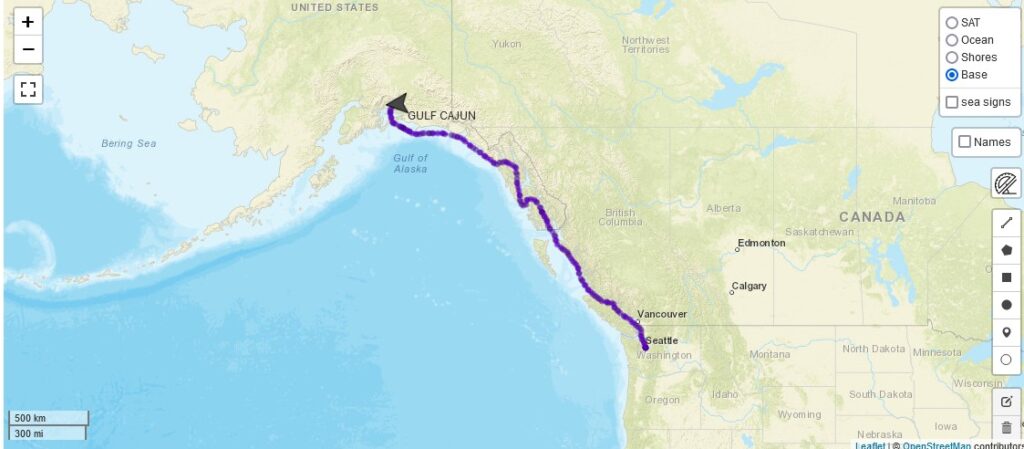

The container sat in Seattle for awhile before being loaded onto the Gulf Cajun for barge passage to Alaska. This route meandered along the coast and among the islands from Vancouver to Haida Gwaii, through Hecate Strait, into the Alexander Archipelago, then across the northern Gulf of Alaska and eventually to Seward. There, it had to meander about the bay for days waiting for space at the dock before the container was offloaded and its long sea journey was over. It was now the end of February.

Then we just waited on emails and the telephone to learn when the container would arrive by land in Fairbanks. It was delivered to the museum on a frosty morning on 15 March, almost four months to the day since we’d packed it.

Then we just waited on emails and the telephone to learn when the container would arrive by land in Fairbanks. It was delivered to the museum on a frosty morning on 15 March, almost four months to the day since we’d packed it.

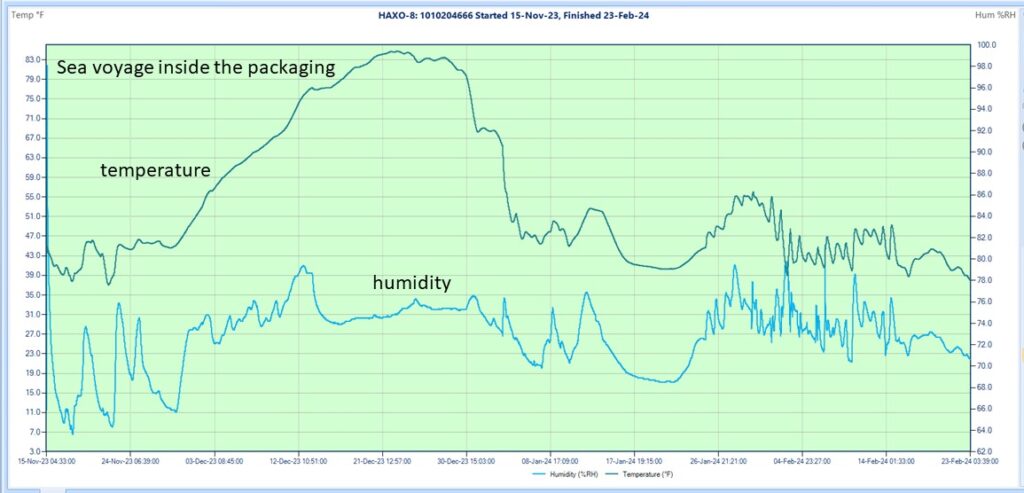

We unpacked the load as quickly as we could to get it into a climate-controlled and secure environment. We’d put temperature and humidity loggers inside for the trip. The data they produced were quite interesting. Good packaging for such a journey is very important; it moderates temperature and humidity fluctuations fairly well. Now we’re steadily unpacking all those boxes and getting specimens into trays before we sort, catalogue, and integrate them into the collection here.

In addition to being an important northern Palearctic collection, the Erritzoe material also includes many rare species from birds that died in captivity. This kind of specimen salvage provides important research opportunities on species that are rare in the wild. Modern specimen material of these species is also usually rare in collections, causing them to be in high demand by researchers. Globally, museums have an important role to play in this area so that we collectively have an improved ability to better understand, manage, and hopefully even recover wild populations.

The Erritzoe collection move is bittersweet. On the negative side, we’re seeing an accomplished ornithologist hanging up his spurs after a lifetime of high-quality work. On the positive side, the gold mine of specimens and associated data that he’s developed has a bright future as scientific fodder for many researchers going forward.

So many birds! How beautiful for Johannes and family to donate them to UAF for future generations.

The odyssey had so much detail, with some pain but in the end, so much joy. It’s a great story and tribute to your perseverance, fortitude and tenacity! Thank you for sharing!

I have been lucky to spent one week holiday at the House of Birds Research with my family back in 1997, enjoying Helga and Johs wonderful and generous hospitality. I am so happy to read that their birds skins, skeletons and related material have found their way to UAF where they could continue to be precious to researchers in the wide world. Johs dedication and skills is an example to future bird enthusiasts and researchers, and the unpredictable hardships to move his collection from Taps to Canada I am sure are worth all the efforts. The epic voyage of the container is worth to be the argument of a book, and remind me of the moving of Lord Rothschild collection from Tring to New York under the supervision of professor Erns Mayr.

The world of ornithology owes Johannes Erritzoe

a very great debt of gratitude for a life well spent in making major and significant contributions – not least of which is the magnificent gift of his meticulously prepared (I saw them at his home many years ago) and scientifically invaluable bird skin collection. Thank you Johs.