Increasing the scientific bang for every research dollar spent is important, especially in museums, where funding levels are perennially low. When we do get into the field and get our hands on a bird, it costs about the same to bring it home with us as it would to return with just a few drops of blood or a couple of feathers. While there is little difference in the initial cost, there is a huge difference in the scientific potential of the effort’s product: many more scientists can do a lot more things with a whole bird preserved as a specimen than with only a tiny sample likely to be quickly depleted. And the vast majority of bird populations can easily withstand the relatively small amounts of scientific collecting that are done these days.

A duck specimen we call Super Pato (Super Duck in English) is a great example of how the rich scientific potential of whole-organism sampling can be achieved. I should note that the scale of this achievement comes without being planned—it comes as a result of having the preserved bird to work with, again and again. This specimen has been divided into multiple collections, one here at the University of Alaska Museum (UAM 19003), another in the Coleccion Boliviana de Fauna in La Paz, Bolivia (CBF-3780), and some of its passengers are archived at the USDA-ARS Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory in Athens, Georgia and at the Illinois Natural History Survey in Champaign, Illinois. This specimen is a Cinnamon Teal (Anas cyanoptera). It happened to be carrying the first wild-origin avian influenza virus isolated from the continent of South America (Spackman et al. 2006, 2007). Quite apart from that interesting discovery, the phenotype and genotype of the duck itself have been carefully studied. It has played a role in a total of seven publications thus far, and email correspondence indicates that it will be part of still more. The lesson of Super Pato is that to maximize the benefits to science, bring ‘em back whole.

The scientific legacy of Super Pato (as of 19 August 2014):

McCracken, K.G., C.P. Barger, M. Bulgarella, K.P. Johnson, S.A. Sonsthagen, T.H. Valqui, R.E. Wilson, K. Winker, & M.D. Sorenson. 2009. Parallel adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia in the major hemoglobin of eight Andean duck species. Molecular Ecology 18:3992–4005. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04352.x.

McCracken, K.G., C.P. Barger, M. Bulgarella, K.P. Johnson, M.K. Kuhner, A.V. Moore, J.L. Peters, J. Trucco, T.H. Valqui, K. Winker, & R.E. Wilson. 2009. Signatures of high-altitude adaptation in the major hemoglobin of five species of Andean dabbling ducks. American Naturalist 174:631-650. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/606020

Spackman, E., K. McCracken, K. Winker, and D. Swayne. 2006. Avian influenza virus found in a South American wild duck is a precursor to the Chilean 2002 H7N3 poultry outbreak, contains genes from North American wild bird and equine lineages, and is adapted to domestic turkeys. Journal of Virology 80:7760-7764.

Spackman, E., K. G. McCracken, K. Winker, and D. E. Swayne. 2007. An avian influenza virus from waterfowl in South America contains genes from North American avian and equine lineages. Avian Diseases 51:273-274.

Wilson, R.E., T.H. Valqui, & K.G. McCracken. 2010. Ecogeographic variation in Cinnamon Teal (Anas cyanoptera) along elevational and latitudinal gradients. Ornithological Monographs 67:141–161.

Wilson, R.E., J.L. Peters, & K.G. McCracken. 2013. Genetic and phenotypic divergence between low- and high-altitude populations of two recently diverged Cinnamon Teal subspecies. Evolution 67:170–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01740.x.

Wilson, R.E, M. Eaton, S.A. Sonsthagen, J.L. Peters, K.P. Johnson, B. Simarra, & K.G. McCracken. 2011. Speciation, subspecies divergence, and paraphyly in Cinnamon Teal and Blue-winged Teal. Condor 113:747–761. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/cond.2011.110042

GenBank accessions: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term=KGM+486

(Thanks to Kevin McCracken, Rob Wilson, Isabel Gomez, and Kevin Johnson for helping us pull together the story – thus far – on Super Pato.)

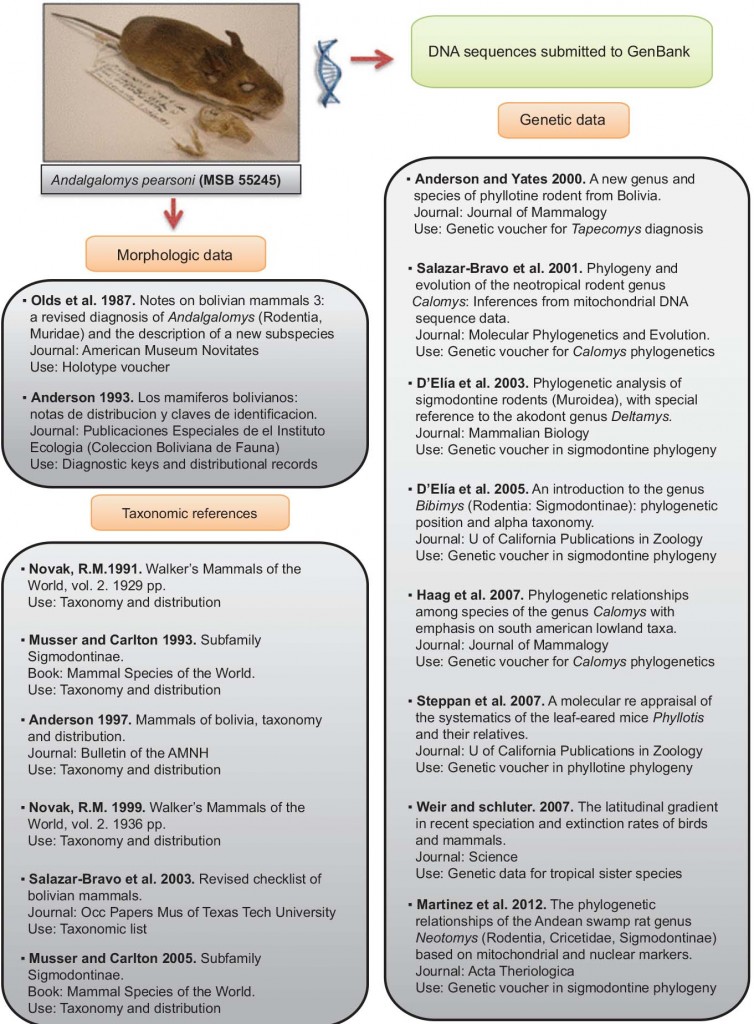

UPDATE 21 August 2014: Jonathan Dunnum wrote to let us know of a similar story (even more impressive, publication-wise) centered on a small mammal specimen at the Museum of Southwestern Biology, published in Dunnum & Cook 2012. (See image below.)

Pedro Viegas writes from Portugal: “We just wanted to say besides being very interesting it also provided a lot of laughs since Super Pato was a cartoon character in Portugal – http://pt.wikipedia.org/

Pingback: Super Pato shows advantages of whole-organism sampling « Thompson Lab of Mammalogy